Senior Deputy Head Mr Hunt discusses intrinsic motivation in girls and the role of engagement, fun and success; how confidence is promoted; and the balancing act between knowledge and skills. How can students find their voice as they take their individual journeys through St Helen’s?

A colleague recently shared an excerpt from Angela Duckworth’s 2016 book, Grit: the power of passion and perseverance as a stimulus for discussion at our fortnightly, staff teaching and learning discussion group. This has not only put it on my radar and my summer reading list, but it provoked a thoughtful, productive and far-reaching debate about what it means for us and our students.

On the one hand we discussed intrinsic motivation in girls and the role of engagement, fun and success, particularly in the early stages of learning. We also considered confidence – how it is promoted, particularly when potentially vulnerable during teenage years, and how academic risk-taking is fostered. How can young women find their voice as they take their individual journeys through St Helen’s?

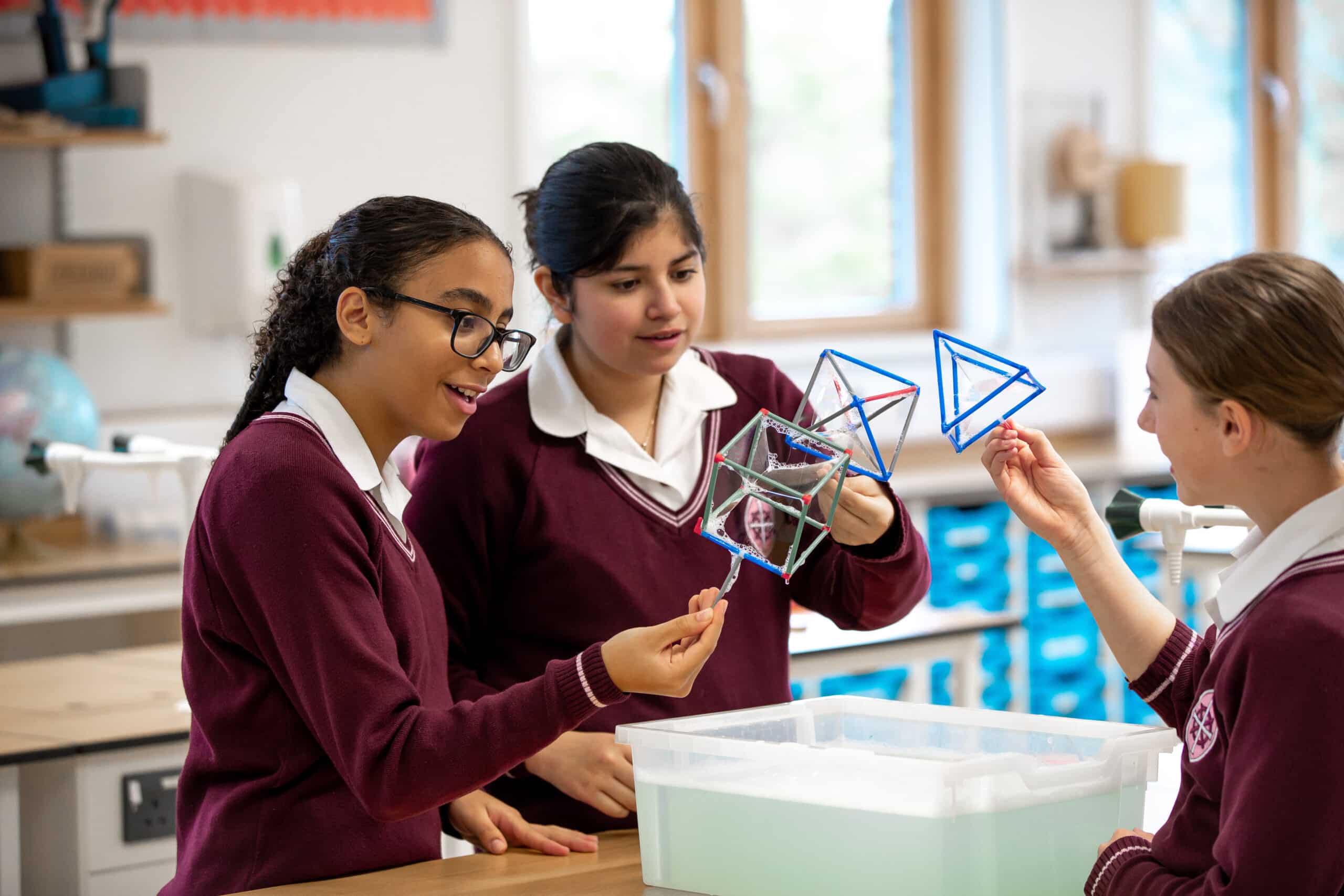

We’d agree that engagement and enjoyment are key to motivation. Experiential learning both in and out of the classroom is at the heart of what we do, be that a science curriculum packed with practical experiments, our outdoor learning curriculum, in-school experiences like Tudor Day, or trips to Lulworth and Cornwall or further afield to Paris and Washington DC. The list goes on and these sorts of experiences and opportunities, designed as girl-centred, successfully encourage students to roll up their sleeves, learn by doing and develop their confidence, unconstrained by external pressures and expectations.

Professor of cognitive psychology, Daniel Willingham’s brilliant, though awfully titled, book, Why students don’t like school, identifies that we are motivated by solvable challenges as long as they don’t feel like they are insurmountable from the outset. We might derive pleasure from a quick sudoku, but most of us will struggle with, and quickly abandon, a cryptic crossword without prior experience or support.

We know that this plays out in the classroom – our very able students evidently have a higher challenge threshold than many, so we have made challenge an area of focus for teaching staff this year. How do we ensure that our students, who are highly capable, are consistently stretched to the right degree, and nudged with gentle course corrections when they are attempting to unpack something truly tricky? I’ve been fortunate enough to see it in lessons: Year 7 historians debating the long term impact of Magna Carta through the lens of Pitt, Roosevelt and Bingham; the range of Year 8 physics Eureka projects, from centripetal force in playground equipment to vibrational nodes and stationary waves in tennis racket design; Year 10 discussing the socio-economic causes of homelessness in German; Sixth Form Further Mathematicians experimenting with game theory and its applications.

Getting this right is key to building confidence and enabling students to flourish in school and beyond. Here too, we can leverage our specialism in girls’ education to provide an environment where all our students find their voice regardless of personality type.

Most recently I have been fortunate enough to participate in a series of vivas hearing from our Year 8 students about their diverse Going Beyond projects. It has been an absolute pleasure because the quality of research and argument has been impressive. I have heard about the opportunities and threats of AI, a range of arguments on the ‘most significant’ event of 2024 and the validity of role modelling in sport, as but a few examples. Eloquent, informed, analytical and robust would be appropriate adjectives for the discussions we have enjoyed – an early foreshadowing of the EPQ presentations of the future, which are always such a pleasure from the Upper Sixth.

Perseverance and practice are at the core of this journey and the heart of what we are here for – working with your daughters to help them develop into the young women they will become: erudite, eloquent confident and well-equipped for the 21st century.

Equally, this association of motivation with success chimes well with, in which he identifies that humans generally don’t like to have to think too hard/much but can be successfully motivated by solvable challenges as long as they don’t feel like they are insurmountable from the outset. We might derive pleasure from a quick sudoku, but most of us will struggle with, and quickly abandon, a cryptic crossword without prior experience or support.

Why learn anything anyway?

Returning to Willingham though, we don’t like thinking too much/hard because we are better wired to rely on memory to fill the gap. “Really?”, I hear you ask – but it’s 21st century – surely, it’s more important to be able to use the right AI prompts to get Chat GPT to tell us what we want to know and then to have vital skills like collaboration and creativity and critical thinking to apply it than it is to actually learn anything?

No, sorry, I’m afraid not. The trouble is that learning information – properly learning it – not only makes us more knowledgeable but it also, sort of, makes us smarter. According to John Sweller and others, all our working memories – our cognitive capacity to manipulate information and hold new material, as yet unlearnt – are all rather small. Typically, we can hold 5-9 pieces of new material in our brain at any one time and really no more (unless we know some particular ‘hacks’ that allow us to cheat). However, material that we have properly learnt – that which finally resides in long-term memory – takes up negligible cognitive space in our working memory.

We can dust it off, wheel it out and deploy it fairly straight-forwardly. Consequently, if we are building an argument writing an essay/answering complex questions from information we really know, we can deploy all of that limited working memory resource to the ‘how’ part of complex processing. If, however, we are relying on a raft of information we have just received from Chat GPT/Google then we are ‘using up’ our working memory to just grasp its relevance and meaning and thus we have far less capacity to do anything clever with it.

So, for those of you with daughters in Years 11 or Upper Sixth who are in the throes of exams, that revision will not only have been a necessity in preparation for working in exam conditions, but it will also have helped them reach a cognitive peak in those disciplines.

Surely skills are more important?

“But what about ‘21stt Century Skills’?” I hear you cry? The World Economic Forum has been telling us for ages that this is what our children need, and that education is failing them – surely not at St Helen’s?

Yes – skills are important, and I’m absolutely on-board that we should be helping students develop them; however, without knowledge how can you develop (m)any skills?

How can you think critically without having confident knowledge of subject-specific material to apply this to – or for that matter some cultural capital to contextualise it? If you are collaborating, what are you collaborating on? If no one in the team knows or learns anything about the project you are working on, your collaboration may not be the most fruitful. I guess you can be creative without prior domain knowledge, but read Martin Robinson’s Trivium and you will see his example of the positive impact of theatrical knowledge on the creative process. In fact, there are those (me included) that see skills themselves as ‘procedural knowledge’ as, for that matter, are certain character qualities which we equally value as part of the St Helen’s education – you learn them: you can learn to be more curious, confident, tenacious, independent.

So, the three – knowledge, skills and character qualities – are very much intertwined and I’d argue there’s very little about most of them that makes them particularly exclusive to the 21st Century – leadership, collaboration, adaptability, creativity and so on have surely been valued for quite some time.

On a day-to-day curriculum level, we work with your daughters on all of these areas. In and out of the classroom the balancing act between knowledge and skills is one all teachers navigate. Both need to be developed in harmony alongside opportunities to develop and learn academic independence; to become more collaborative, to begin to become more confident in communicating to peers, taking a lead and developing tenacity in the face of setback.