In this article, Senior Deputy Head John Hunt explores the substantial body of research supporting the advantages of girls-only schooling, highlighting its role in fostering academic excellence, confidence and leadership.

As a School which has identified its specialism in the education of girls and young women as its ‘superpower’, it is no surprise that we are interested in the substantial evidence base that supports our advocacy of single-sex education.

A robust body of research suggests that single-sex education, especially for girls, offers unique advantages that empower them to thrive academically, socially and personally. We see the strength of the former every day, and the benefits to our students, as our specialism in catering to the particular needs of adolescent girls and young women remains, as it always has, at the heart of what we do.

Nonetheless, the issue remains complex: some advocate for co-education as a reflection of a more modern and equal society. However, this viewpoint often overlooks the persistent structural obstacles and stereotypes that females continue to face (Robinson et al, 2021). Surely, these are obstacles that we should not be looking to emulate as girls are growing up but rather creating an environment in which they are best equipped to navigate and overcome them. To draw an academic parallel, students don’t get better at writing complex analytical essays by being set such tasks in full as novices – there’s a better process to the acquisition of knowledge and skills through careful teaching to engender confidence and progression.

This superpower is one that we don’t take lightly and one whose benefit is not only felt experientially in our community but is borne out by a range of recent and relevant academic studies.

One of the most compelling arguments for single-sex education lies in its ability to challenge and disrupt gender norms. Girls’ schools create a space where girls are not limited by societal expectations or stereotypes, fostering a learning environment conducive to their individual growth and development. This is particularly crucial in today’s world, where girls are bombarded with conflicting messages – to be both ‘mighty and good’ – leading to anxieties over image and self-doubt (Filipovic, 2017).

A consistent theme emerges from the various studies: girls in single-sex schools demonstrate higher academic achievement and exhibit greater academic engagement than their co-educated peers. For his report for the Girls’ Day School Trust (GDST) in 2019, Dr Kevin Stannard drew from a wide range of longitudinal studies to highlight Riordan’s (2015, p.28) conclusions that, ‘Across a wide range of high-quality studies, students in single-sex schools, compared to their counterparts in coeducational schools, have been shown to have higher academic achievement and more favourable (sic) socioemotional outcomes.’

Similarly, Stannard highlighted Laury, Lee and Schnier’s (2019) appraisal that: ‘a growing body of evidence suggests single-sex education can improve student performance, be it math skills and self-confidence, test scores and college attendance, or grades and pass rates. Just look at the disproportionate number of top league table positions occupied by girls’ schools’.

Stannard is supported too by Department for Education (DfE) data for England for the past two years, highlighted in a 2025 GSA report, which continues to point to students of both sexes achieving better at GCSE and A level in single sex as opposed to co-educational environments.

This correlates with Robinson and Gillibrand’s (2004) finding that single-sex classrooms benefitted affluent students academically, while Daly and Defty (2004) showed that although girls excelled at GCSE in these settings, boys performed worse compared to those in co-educational classes.

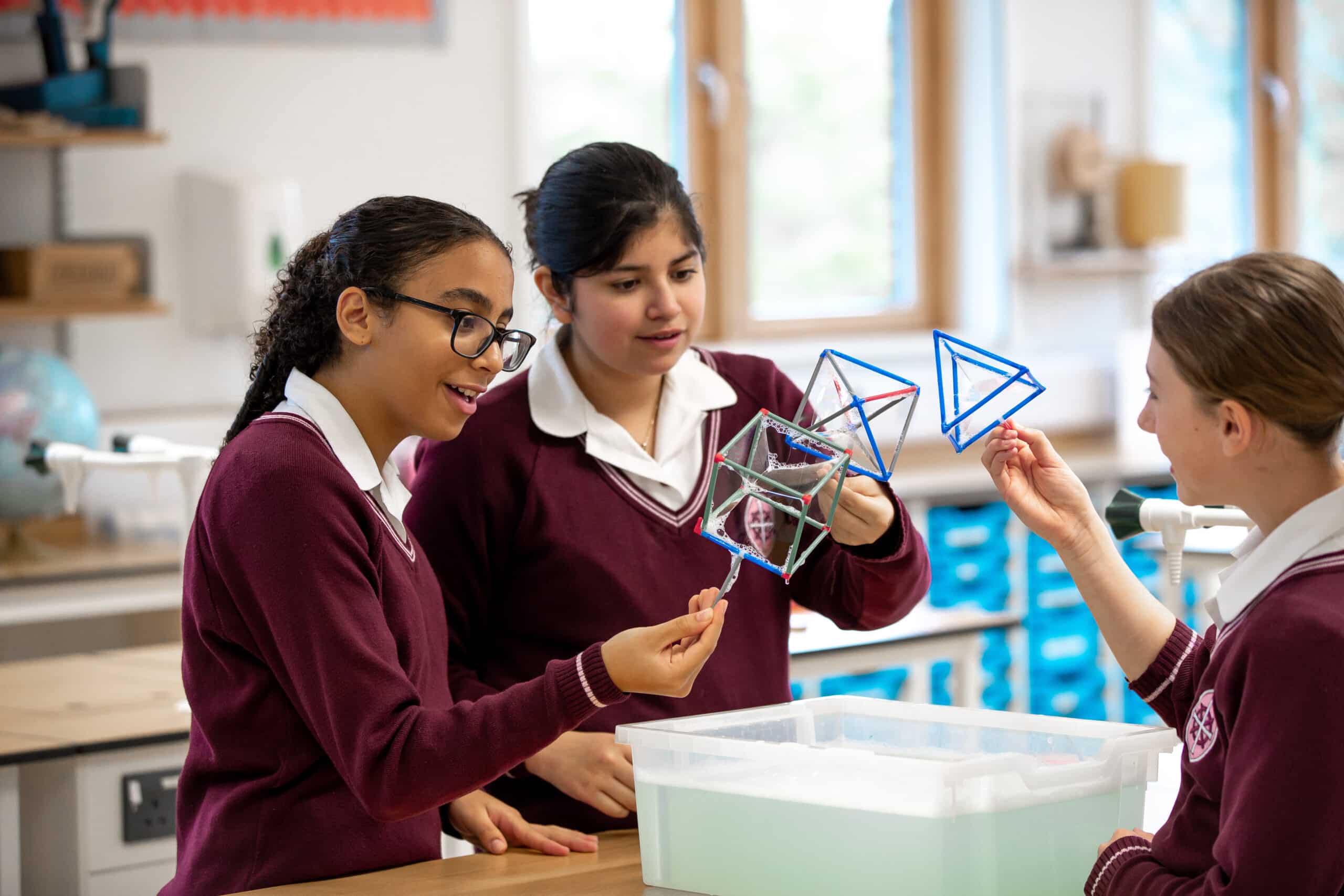

Beyond results, single-sex settings cultivate greater diversity in subject choice for girls, especially in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) fields. Research has consistently shown that girls in girls-only schools are more likely to pursue and excel in subjects traditionally dominated by boys.

It is certainly true here, as it is across the Girls School Association (GSA), where a significantly higher percentage of students take A level Mathematics, Chemistry, and Physics compared to national averages for girls. The same 2025 GSA report, drawing on the DfE and the Universities and Colleges Admissions Service (UCAS) data recorded that girls in all-girls Sixth Forms were 2.9 times more likely to take Further Maths than those in co-educational settings and 2.3 times more likely to take Physics. They were 83% more likely to take Chemistry and 79% more likely to take Computer Science.

The higher take-up of STEM subjects in single-sex schools then often translates into girls’ higher education (HE) and future career choices: 4 times more likely to take Maths courses, twice as likely to take Physical/Biological science courses and 40% more likely to pursue engineering. And these are stats borne out by looking at the number of our leavers going on to medicine and STEM courses and professions.

Fifty percent of all-girls’ school alumnae have worked in a STEM-related field in their career, despite women accounting for only 8% of the STEM workforce. Likewise, research demonstrating the positive academic premium on the wages of women who attended single-sex schools, attributed to their strong performance in post-16 qualifications.

Not only do girls’ schools mitigate the threat of stereotyping when it comes to subject choice, HE and careers, but they amplify wider opportunities for girls to step outside traditionally prescribed gender roles and fully embrace developing their skills and talents. Girls in single-sex settings are more likely to take risks, seek alternative solutions and throw themselves into leadership opportunities – they are surrounded by relevant role models to whom they relate: after all you can’t be what you don’t see.

A recent study by Miller et al. (2023), supported by Bajaj (2009), found that girls from single-sex schools were 30% more likely to take on leadership roles in university or professional settings compared to their coeducated peers. The study emphasised that these schools provide platforms for girls to lead in various domains, from sports teams to academic societies and we certainly see this from the feedback of our alumnae community.

Moreover, Cribb and Haase (2016) found that girls in single-sex schools demonstrated higher levels of self-worth and body image satisfaction than their peers in coeducational schools. This is critical during adolescence, a period when societal pressures about appearance and behaviour can undermine self-confidence. Girls in girls’ schools not only display greater intrinsic motivation compared to boys in single-sex schools but also surpass girls in co-educational schools in both self-esteem and achievement motivation (Cherney & Campbell, 2011).

Girls’ schools provide an affirming environment where girls can develop a strong sense of self, challenge limitations and cultivate their aspirations without the distractions and pressures present in mixed-gender environments. Girls-only schools cultivate a strong sense of community and belonging on female terms, contributing to improved social well-being and mental health. Studies have even shown that girls in single-sex settings experience less bullying and harassment, leading to increased confidence and self-esteem.

Girls’ schools, like ours, give girls space to think, grow and thrive.

Prioritising the needs and challenges of girls in a dedicated space is all the more important as the “boy turn” in educational research has often led to teaching approaches and curriculum content that inadvertently favour boys’ (stereotyped) preferences, potentially leaving girls feeling overlooked or undervalued.

Single-sex environments enable teachers to deliberately design pedagogical approaches that cater specifically to girls. For example, girls seem more likely to thrive in collaborative, discussion-based learning environments, a style that is more easily accommodated in single-sex settings (Spielhagen, 2008). A GDST report (2016), rightly recognises that these approaches are not necessarily girl-specific, but ‘girl friendly’ and enablers of girls maximising their potential. This report too discusses the importance of challenge and support, dialogic approaches and giving girls time and space for prolonged activities that allow more developed and considered responses.

Equally, girls in single-sex institutions tend to receive more attention in lessons, leading to enhanced opportunities to bolster confidence (Hartman, 2010), whereas in co-educational classes, even the best teachers end up interacting more with the boys: between 10 and 30 per cent more attention is paid to boys than girls in a co-ed classroom, particularly in Science and Maths. Moreover, research has revealed the prevalence of gender bias in perceptions of ability, with girls’ performance often underestimated compared to boys, even in fields like Mathematics.

It’s important to recognise that merely separating girls from boys does not automatically translate into positive outcomes. For single-sex education to be truly effective, it must be accompanied by a conscious and intentional approach to curriculum design, pedagogy and school culture – which is exactly what we do.

Single-sex education, when implemented with intent and commitment, provides girls with a powerful pathway to success. It equips them with the tools and support necessary to thrive academically, socially and personally, empowering them to become confident, resilient and capable individuals ready to make their mark on the world.

We remain clear and dedicated regarding what we do and why and how we do it – that’s not going to change: the benefits are significant, well supported academically and highly visible.

We celebrate each and every student completing her journey here, and leaving us for successful, interesting, exciting and diverse endeavours – on her terms.